Big Savage Tunnel

somerset | Meyersdale, PA Mile 22

The Nuts & Bolts: Big Savage Tunnel

• 3,294 feet long

• Original Construction: completed in 1912

• Rebuilt for GAP Use: December 2003, climate doors added in 2005, opening ceremonies occurred in 2006.

• Total Cost: $11,600,000.00

• Engineer: Gannett Fleming

• Contractor: Advanced Construction Techniques (ACT)

• Project Manager: Rolland “Rhody” Rhodomoyer

BST Material Fast Facts

- Cellufoam Grout – 6,000 cubic yards

- Shotcrete Liner – 1,650 cubic yards

- Rivets (for drainage layer) – 200,000 (3” rivets 9.5 miles)

- Drainage Pipes – 3,000’ of 15” ADS; 5,000’ of 10” ADS

- Drainage Layer – 42,900 feet of drainage layer and back mesh

- Rock Bolts – 7,000 total

- (52,800 feet of 8’)

- (49,500 feet of 12’)

- 19.4 miles of rock bolts

On the Sunday night after George Cook’s family became the first to pedal through the Great Allegheny Passage’s newly reconstructed Big Savage Tunnel, he received a call from a reporter at the local paper. “One of my big interests in the trail was always to leave something for posterity,” the 83-year-old told The Daily American’s correspondent, Sandra Lepley.[1] Cook, then-president of the Somerset Trust, was a long-time supporter of the Somerset County Rails-to-Trails Association (SCRTA) and served on the Allegheny Trail Alliance (ATA) board.[2] When fellow SCRTA member Paul g Wiegman came up with the idea to auction off the first official ride through the tunnel, Cook’s six sons jumped at the chance to win the experience for their dad as an early Father’s Day gift.[3]

On April 8, 2006, a rainy Saturday morning, four generations of the family rode through the tunnel. George Cook was supposed to be first to ceremoniously pass through the portals, but, as the photos from the day captured, his four-year-old great-grandson Zachia raced to the front of the pack as they neared the tunnel’s end. “Zachia is an example of the future generations who are going to enjoy” the tunnel, Cook told Lepley, and “We were very pleased with the day.”[4]

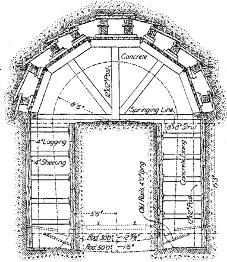

This celebration, which was followed by a dedication ceremony in May, was the delayed gratification at the end of a long, costly rehabilitation. The tunnel was originally constructed in 1912 for the Western Maryland Railway to connect Maryland and the Mason-Dixon Line to Pittsburgh. At 3,294 feet long, the Big Savage Tunnel is the longest on the Great Allegheny Passage and provides unhindered travel through Big Savage Mountain.[5] When it was built in the early 20th century, the railroad used the same “O’Rourke” system of airlocks that New York City was using to build their subway system.[6] This method controlled the flow of mud and sand in a small river system 600 feet from the tunnel’s western portal, adding air pressure at 20-35 pounds per square inch.[7] Due to breaches of sediment and water during the course of the original construction in February of 1911, an additional tunnel section was dug to provide space for a concrete liner and structural invert in an effort to seal off the tunnel from the loose soil with the already constructed “timbering” that was placed earlier that previous year.[8] A diagram showcasing the original tunnel design illustrates the additional liner and supporting timber. Specialized workers called “sand hogs” were trained to work in these pressurized situations so they could reinforce the tunnel with concrete lining.[9] The problem of the sand and mud flow continued to plague the tunnel for decades, requiring many costly repairs until the line was abandoned in 1975.[10]

Linda M. Boxx, president of the Allegheny Trail Alliance led the efforts to raise funds and build the trail through the tunnel, which proved to be the only viable option for navigating Big Savage Mountain without rerouting or segmenting the trail. The first major obstacle was raising enough money to pay for the rehabilitation of the structure. As a nonprofit, the ATA relied heavily on private grants and state funding to complete sections of the trail up to this point. Initial surveys of the tunnel called for total reconstruction and rehabilitation at a $2.5 million price tag.[11] Finding sufficient funds was already a serious concern and was further exacerbated by a more formal evaluation that escalated the estimated cost of reconstruction to nearly [12]

On April 7, 1997, Boxx drove to Harrisburg for a meeting with John Oliver, Secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and National Resources[13], to discuss the tunnel’s mounting price tag.

“At this meeting he said, “Well, you need to go see Rick Geist.” And, I said, “Oh, okay, well, the next time he comes to Harrisburg, we’ll make an appointment.” He goes, “You don’t need an appointment. Just call his office and see if you can get to see him this afternoon.”[14]

By 3:00 PM Boxx found herself sitting across from Representative Rick Geist, State House Representative for Altoona and the chair of the Transportation Committee. Geist was also a passionate bicyclist, and within 15 minutes he had directed his staff to insert two line items for the trail into the state capital budget – a $6 million line for the construction of the Big Savage Tunnel and another $10 million for trail construction. When the budget passed, the line items were included in the DCNR’s capital improvement budget.[15]

The second hurdle was the construction of the tunnel itself, which had a myriad of its own problems. Years of neglect created rampant issues of moisture and uneven soil in the tunnel. Big Savage Mountain is a large aquifer that produces a constant flow of water and residual moisture. Mixing that moisture with seasonal freezing and thawing conditions degraded the integrity of the tunnel, causing damage to both the north and south entrance portals.[16] Both portals developed “dams” of mud, creating a waist-deep pond of water around waist-deep. It was essential that the tunnel undergo a proper assessment and rehabilitation.[17] To tackle this challenge Project Manager Rolland “Rhody” Rhodomoyer, who had just retired after working thirty-eight and a half years for the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation and DCNR as a surveyor/construction manager, came out of retirement to see this project through.[18]

The Pennsylvania Department of General Services funded engineers from AWK Group of Companies to perform a walkthrough to assess the full extent of necessary repairs. When the project was bid out, Advanced Construction Techniques (ACT), a Canadian construction company, won the contract to take on the project. In their own assessment of the tunnel, ACT brought on Gannett Fleming as an engineering consultant to adjust the plans to correct AWK’s design. The original project plan did not address all the drainage and freeze-thaw problems which, if left unaddressed, could have required extensive maintenance even after the tunnel was rehabilitated.[19] While the overall cost increased to meet the budget demands and material fees, the choice to modify the plan in accordance with ACT’s findings proved beneficial in the long term.

Another major challenge associated with the structure of the tunnel concerned a narrow gap between the rock walls and the tunnel liner, making the tunnel even less stable than previously thought. To fix the problem, the concrete liner needed to be rock-bolted into the rock tunnel walls with around 7,000 rock bolts. To seal the gap between the tunnel liner and rock tunnel overhead, workers used Cellufoam along the full 3,295-foot length to minimize rock falls and increase resistance to moisture. Brett Hollern, Trail Coordinator for Somerset County at the time of the Big Savage Tunnel’s rehabilitation, compared the configuration to a “giant Twinkie,” with the Cellufoam layer being the filling that glued the overhead rock and tunnel liner together.[20] Both north and south entrance portals were cleared of sediment and insulation was added, with custom-made folding aluminum doors installed in 2005 by Somerset’s own Weimer’s Blacksmith & Welding. This allowed for sealing the tunnel during the winter months.[21] As a final precaution to keep the interior of the Big Savage Tunnel sealed, workers applied a cement material layer to the tunnel layer to limit any pervasive moisture that may have bypassed the rock bolting and insulation.[22]

In February of 2002, the Big Savage Tunnel reconstruction project was in dire straits. The damage within the tunnel revealed itself to be more significant than previously assessed, pushing back the completion date twice and requiring additional funding to match the rising cost of the project, which at that point approached $9.8 million.[23] Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Secretary John Oliver with the much-needed assistance of Land and Water Conservation Fund Director Larry Williamson[24] were able to secure state grants to meet the escalating costs, drawing from the Land and Water Conservation Fund which secured another $2 million dollars on the public level.[25] Private funding, such as support from the Richard King Mellon Foundation, the Heinz Endowments, the Hillman Foundation, the McCune Foundation, the Laurel Foundation, Columbia Gas, the Katherine Mabis McKenna Foundation, and 374 other individual donations, helped meet project completion goals and pay for the addition of the aluminum doors.[26] After a total of three construction delays and an ever-increasing price tag, all major construction on the Big Savage Tunnel was completed in December of 2003.[27]

The Big Savage Tunnel for many of the trailbuilders involved was a headache that seemed to progressively change over the course of reconstruction. To put it more into perspective the condition and subsequent hardship the tunnel (and Savage Mountain itself) caused, Rolland “Rhody” Rhodomoyer elaborates on how the mountain itself sometimes played against himself and the ACT contractors:

[W]here the wall came up and the form came down [at the northern portal of the Big Savage Tunnel]. Most of that was all re-poured, that wall, because, you know, the other stuff was crumbling. But, what was funny–the one guy [a contractor from ACT] went into the north portal and he said, “I’ll have this thing out of here in three hours.” He wasn’t out of there in four days. And, you know, there was no steel in it. All it was is what I like to call “river biscuits,” just little round stones. And, that’s all it was. And, he could not get through that. They ended up bringing a big […] jackhammer on it to actually finish it. I guess, they figured four or five days was too long.[28]

To say rehabilitating the Big Savage Tunnel was a challenge is a vast understatement. Without the proper construction or necessary funding, there would have been neither a passage through Big Savage Mountain nor an easy route to continue onto different sections of the trail. The Big Savage Tunnel was the concrete backbone of the Somerset section, a vital connection for recreation and tourism in both Western Pennsylvania and Maryland. Perhaps it was destiny that the tunnel, drowned in settling water and left to deteriorate by its Western Maryland creators, was repurposed and revitalized by the Allegheny Trail Alliance and their vision for the Great Allegheny Passage.

Author: Reed Hertzler & Avigail Oren .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... VIDEO: WQED Pittsburgh produced this short feature on the Big Savage Tunnel, as part of its project, "The Great Ride" and is used with permission.