In the late 1980s, a group of Somerset County leaders met with then-Congressman John P. Murtha to hear about the county’s priorities. Murtha always focused on economic development because the decline in the steel and coal industries had damaged the area’s economy.

Murtha was genuinely surprised when Hank Parke, head of the Somerset Chamber of Commerce, said their biggest priority was a trail.

This was not just any trail. It was the county’s piece of what today is the Great Allegheny Passage. At the time, none of it was built. It was just an idea. But it was an idea that Parke enthusiastically embraced, articulating how this trail could bring in tourists from far and wide.

Murtha passed away in 2010 after serving 36 years in Congress, much of it as chairman and or ranking minority member of the House Subcommittee on Defense Appropriations, a post from which he had enormous influence domestically and around the globe. He created headlines world-wide when, as a Marine Corps colonel with a career as a hawk on defense issues, he came out against the war in Iraq.

But back in the late 1980s, Parke pitched Murtha about building this trail. His pitch centered on America’s Industrial Heritage Project, an initiative that Murtha created and funded through the National Park Service to preserve and interpret a nine-county section of Southwestern Pennsylvania where America had become the greatest nation on earth through our industrial might.

“We were meeting with Congressman Murtha and said, this is really a nine-county area, what about some projects in Somerset County,” Parke said. “That really got us connected with AIHP and that got us our first money to do this feasibility study, which said, ‘do it.’”

AIHP funded not only the feasibility study, but also the development the first few trail sections outside of Ohiopyle State Park. As one of the county’s first rail-trails, the park had built 9.5 miles of trail on the old Western Maryland Railway line by 1986.

Seven years later, seven miles of Allegheny Highlands Trail opened in Somerset County from Rockwood to the Pinkerton Low Bridge at a cost of more than $400,000 and 2.5 miles of the Youghiogheny River Trail opened in adjacent Fayette County at a cost of $243,500. Both sections were designed and built with AIHP money.

At the groundbreaking for the Rockwood section on April 24, 1992, Murtha said, “These hiking and biking trails provide a great recreational opportunity for area residents so they improve our quality of life. But these trails also have an enormous potential to bring visitors to our region – and once they see how beautiful these mountains and rivers are, I’m confident they’ll keep coming back.”

Murtha added, “Many people perhaps don’t realize the historical significance of these old railroad rights-of-way. So we’re preserving something of importance but we’re also creating new opportunities – recreational opportunities not only for our own people but for hiking and biking enthusiasts from around the nation.”

Hank Parke often told the story how Congressman Murtha helped Somerset County save the Salisbury Viaduct. When Route 219 was undergoing major improvements in the 1990s to expand to a 4-lane highway near Meyersdale, PennDOT wanted to remove the superstructure of the Salisbury Viaduct so the highway could pass through unobstructed. Hank was distraught, to say the least, and turned to Congressman Murtha for help. The end result was that the northbound and southbound lanes each easily passed between pairs of bents of the trestle, saving a signature structure of the GAP from demolition.

Pat Trimble at the time was mayor of little Dawson Borough and a vocal trail advocate. Trimble reflected on AIHP and Murtha’s impact, saying, “There was no other avenue (for funding), that’s the only way it would go through. We had to go to I forget how many meetings, 3 or 4 a month, to meet the county people and AIHP people. Then everybody started dancing at the same time.”

“The Regional Trail Corporation (RTC) was successful in lobbying for America’s Industrial Heritage Project (AIHP) funds for early trail development of the Yough River Trail North. These funds seem to have been heaven sent, in that; we had much of the trail designed from Boston to Connellsville but with no funding for construction.

The AIHP funds were very significant, several hundred of thousands of dollars, and somewhat unrestricted which allowed us to pick and choose what and where we would use these funds. We The RTC collectively decided to use the funds to construct trail segments near populated areas in Allegheny, Westmoreland and Fayette counties. This decision was made to show communities as well as political entities that trails would be a good thing. There were many skeptics toward developing trails in the early years.”

-Interview with Jack Paulik on June 25, 2020

Over a five-year stretch, from 1990 through 1994, $2.5 million was funneled to develop some easier sections of the GAP Trail in Somerset, Fayette, Westmoreland, and Allegheny Counties, PA.

Completion of those trail segments was critical to build momentum for more challenging trail segments, such as the Big Savage Tunnel and the Pinkerton High and Low Bridges.

In 1991, Congress passed the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act known as ISTEA containing the first of what was known as “transportation enhancement” funding. Historic preservationists had pressed to get a portion of all highway-construction dollars set aside for preservation of historic buildings and for walking and bicycling improvements to compensate for the loss of such assets when many highways were built with virtually no regard for historic preservation.

The passage of transportation enhancement funding in 1991 was fortunate for two reasons.

First, several massive and very expensive GAP projects required more money than the amounts available for trails through AIHP.

Second, from 1988 to 1993, Murtha was able to get $8 million to $15 million appropriated each year for AIHP, with most of that money going to improve or develop heritage-tourism sites such as Allegheny-Portage Railroad National Historic Site, Fort Necessity National Battlefield, Johnstown Flood Museum, Horseshoe Curve National Historic Landmark, Altoona Railroaders Museum and West Overton Museum.

In 1994, AIHP funding was greatly reduced when another Congressman openly challenged Murtha over the amount of money going to this nine-county heritage area. The annual funding dropped dramatically to $3 million to $4 million a year, with very little of that money going to trails.

ISTEA more than filled the gap, with $9.7 million going to develop the Hot Metal Bridge in Pittsburgh, $1 million to the Salisbury Viaduct, $1.2 million to the Ohiopyle Low Bridge and $1.3 million to four smaller trail sections.

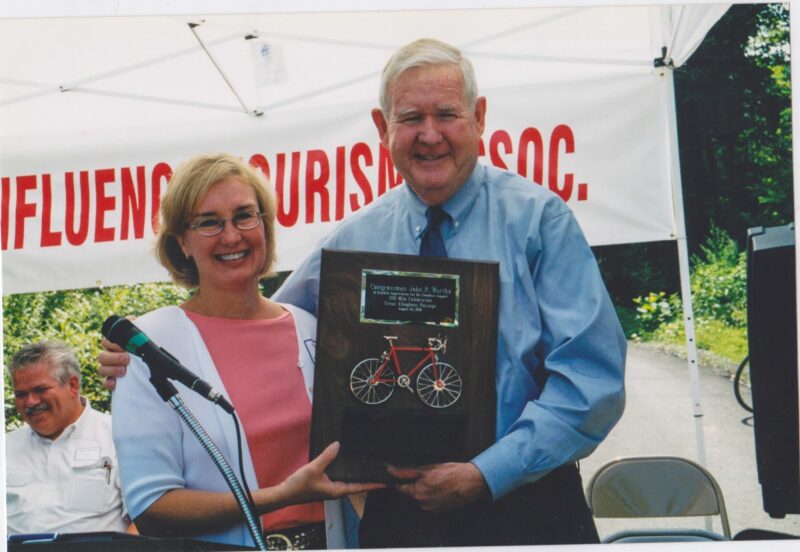

Murtha accepting an award for Linda M. Boxx during the 100-Mile Celebration in Confluence in 2004.

As these projects were being completed in 1998 and 1999, Congress passed the next transportation authorization, this one known as the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century or TEA-21. This legislation generated $6 million for GAP development as a high priority project sponsored by Murtha.

In August 2001, the “Linking Up” celebration recognized the connection that created 100 continuous miles of trail. Then, with $33.2 million spent or committed to the endeavor, $17.2 million was from federal funds, $10.9 million from state funds and $4.8 million from foundations and other private sources.

At the celebration, Murtha spoke as the major proponent of the federal funding and John Oliver, then secretary of the state Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, as the top state official. They linked two chains, one representing the 30 miles of Allegheny Highlands Trail and the other, the 70 miles of the Youghiogheny River Trail, the components of what by then was called the GAP.

“There’s no question that we’re developing a tremendous recreational corridor through Somerset and Fayette Counties stretching right into Pittsburgh and obviously the spectrum of recreational opportunities will attract people, both to play and to live,” Murtha said.

He emphasized that tourism had become Pennsylvania’s second largest industry and that people traveling for outdoor recreation were the largest component of the business, accounting for 19 percent of the leisure travelers and 33 percent of the leisure spending.

Two years later, Murtha again teamed up with Oliver to support the allocation of $2 million for Big Savage Tunnel from the federal Land and Water Conservation Fund, which funnels its money through the states. DCNR had already committed $9 million to the tunnel restoration. In a letter from the National Park Service regional director, DCNR was informed that this allocation had been approved. Larry Williamson, then director of DCNR’s Bureau of Recreation and Conservation, added a hand-written note to the NPS letter when he shared the good news with Murtha and others:

“NPS definitely wants a ribbon-cutting event when project is done. I think we can get the NPS director, Fran Mainella, to attend. We need to start thinking about a date and the logistics.”

Murtha announced approval of the funding in the news release dated Feb. 5, 2003, saying, “This is by far the biggest project on the Great Allegheny Passage, and it was potentially a ‘show stopper’ in making the critical link between Pennsylvania and Maryland. So we’re grateful to the National Park Service.”

Many of the final pieces of the GAP were then funded through the third transportation bill with enhancement funding.

Murtha ran into the late Congressman Jim Oberstar of Minnesota, then the ranking minority member of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee and a trails advocate. Oberstar asked him if he needed some money for “his trail.”

Murtha quickly called his staff (me!) who reached out to Linda McKenna Boxx, then president of the Allegheny Trail Alliance, to ask how the ATA could use $2 million. Boxx told him the biggest priority was to complete the last nine miles of trail in Maryland, where $1 million had been obtained but another $1.5 million was needed. Another high priority project was to eliminate an at-grade crossing in Garrett where a highway bridge over the railroad had been removed years before so walkers and bicyclists would not need to cross a busy state highway at a cost of $800,000.

Members of Congress do not typically go to bat for projects outside of their districts, let alone outside of their state. But by this time, Murtha was such a believer in the trail that he asked Oberstar to include these projects in the transportation bill, which passed in August 2005.

Murtha (center) linking chain at 100-Mile Dedication ceremonies near Confluence in 2004.

At the time, as Murtha’s district director, I asked him if he wanted to put out a news release for projects that were not in his district since his constituents might not understand why he earmarked the money for projects in his district. Murtha never flinched in announcing the funding, talking about “a great stride toward completion of a world-class trail.”

Recently I was myself cleaning out old memorabilia and found a globe of the world. In the box was a small notecard with the handwritten comment, “Thank you for helping me have an impact on world affairs, Jack Murtha.”

For all of the impact that Murtha had on world affairs as chair of Defense Appropriations, he never forgot the need to take care of the folks at home. And for the late Congressman, “home” had a broad footprint the Great Allegheny Passage.

Author: Brad Clemenson (Staff member for Congressman Murtha)