“It doesn’t happen without that, without that synergy, and without everybody helping each other and pulling together. I mean, PA giving Maryland a million bucks, it’s unheard of. So, those type of things really make it. And, it is very satisfactory to say you were part of that. You know, that a part of my legacy as a planner in the State of Maryland is helping to get this trail built.”

– Bill Atkinson, August 10, 2018[1]

The Great Allegheny Passage (GAP) in many ways set an example of what rail trails could be for small towns experiencing economic hardship. Infrastructure once dedicated to industry could be reborn as a pipeline for tourists and recreational development. Spurred by the potential of what the GAP project would (and did) become, Bill Atkinson saw trail development as a saving grace for his hometown and a worthwhile venture to be pursued by the state of Maryland.

Atkinson, a native of Allegany County, Maryland, played around the tracks of the Big Savage Tunnel as a kid in the early 1970s and ’80s – the same tracks that would be transformed into the GAP.[2] Atkinson began working on the GAP when he was hired by the Maryland Department of Planning, just after the National Parks Service (NPS) completed a feasibility study of the trail in 1989.[3] In the early 1990s Atkinson was appointed by Allegany County commissioners to the Allegheny Highlands Trail Maryland Committee to help oversee the trail project as it progressed.

“I mean, I think everybody starts to see what Linda Boxx and those early people that took that original ride saw, that this really could be a game-changer for a lot of places through Western Pennsylvania and Western Maryland, to bring in not only tourists but to bring in business. And, I think that was the time that synergy really started to take hold and take place.” – Bill Atkinson, August 10, 2018[4]

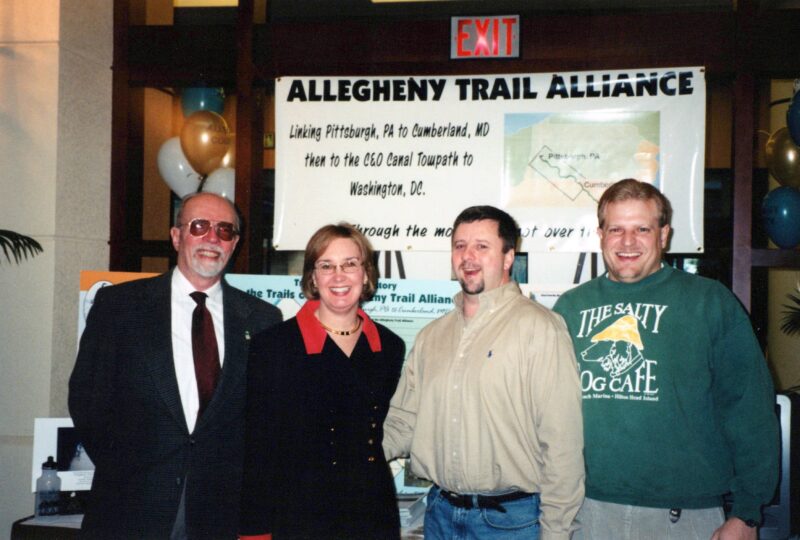

Atkinson (third in from left) at an Allegheny Trail Alliance event with trailbuilders (left to right) Marshall Foshold, Linda M. Boxx, and Dave Cotton.

At that time, the project scope was only from Cumberland, MD to Confluence, PA, and many of Atkinson’s colleagues in the department believed the trail was a “pie in the sky.”[5] During Atkinson’s appointment to the committee, a plan began to form to have the trail span from Cumberland to Pittsburgh, which made more sense for political advocates of the trail and expanded the scope of economic opportunity for trail towns. “[It] really didn’t get embraced more [until] the 1990s when [people realized] ‘hey, this could really work.’”[6]

Atkinson joined the Allegheny Trail Alliance (ATA) shortly after it was formed. He held a seat on the ATA Board of Directors from 1998-2017 and served as president in 2014.

Atkinson (center) with Linda M. Boxx and Tom Murphy at a Hot Metal Bridge event in Pittsburgh.

The strong partnerships that were formed while building the GAP helped to “pave” new regulations in Maryland which are more appropriate for trails. Atkinson believes that cooperation from state officials, local volunteers, and trail groups within the ATA were essential in making a grassroots-based trail project like the GAP possible. Most of the rural towns in Maryland that the GAP was set to run through were “coal towns” that were desperate for new economic infrastructure. Atkinson made sure this was a key factor in gaining support for the project: raising up opportunities for local businesses to grow from trail involvement. And so far, over a decade later, this vision has been realized.

“That’s the other side of economic development the trails bring to your town. They’ll bring industry, they’ll bring business. Businesses will locate here because you have a trail. Doctors will come here because you have that quality of life, that trail. In rural areas, they’re the tough things to get. But, this [Trail Town Program] helps us to get that from that economic standpoint.”

– Bill Atkinson, August 10, 2018[7]

Atkinson (right) with Jack Paulik and Linda M. Boxx during the Point Made! ceremonies in 2013 in Pittsburgh.

After construction was completed in 2006 up to the Mason-Dixon line, Atkinson continued to stay involved with the ATA. From 2009 to 2014, he assisted Linda M. Boxx in establishing a Trail Town Program in Maryland. The Trail Town Program gave local businesses a template to build the GAP into their business models – a partnership that suited the needs of both trail users and small town business owners. This meant providing things such as “trail packages” that included certain resources for bikers and hikers, like special meals or hoses to wash off their bicycles. Atkinson was instrumental in creating a “Certified Trail-Friendly” program to encourage businesses to be accommodating to the needs of the trail visitors. After completing a training session, a gold seal is awarded to the business that completed the program, which could be placed on the door of the business to inform patrons that this “Certified Trail-Friendly” establishment is welcoming and helpful.

This format became a huge success and to this day has helped local businesses in Frostburg and Cumberland (along with smaller trail towns) survive off of the trail in a symbiotic relationship of recreation and economic development.

Bill Atkinson’s October 2005 Video Interview with Paul G. Wiegman

Bill Atkinson’s October 2005 Video Interview with Paul G. Wiegman Transcript

Bill Atkinson’s October 2018 Interview with Eric Lidji Transcript

Author: Reed Hertzler

Endnotes

[1] Bill Atkinson (Maryland Department of Planning, Personal interview on experience building the GAP Trail in Maryland), interviewed by Eric Lidji, Cumberland, Maryland, October 8th, 2018. Transcript: “2018-10-08 Bill Atkinson_Final,” 33-34.

[2] Atkinson, Transcript, “2018-10-08 Bill Atkinson_Final,” 1.

[3] Ibid. 2.

[4] Atkinson, Transcript, “2018-10-08 Bill Atkinson_Final,” 11.

[5] Ibid. 2-3.

[6] Atkinson, Transcript, “2018-10-08 Bill Atkinson_Final,” 2-3.

[7] Atkinson, Transcript, “2018-10-08 Bill Atkinson_Final,” 29.